PSC Overview

Everything you need to know about PSC, its causes and what will happen

Accessing the most up-to-date, accurate information is essential when you have a rare and complex disease like PSC. All of our information is checked by PSC experts and supported by evidence and it is free and easy to access - no registration required.

This is our PSC Awareness Day 2020 video

PSC Overview: Quick Links

PSC is short for primary sclerosing cholangitis. PSC is a rare, immune-mediated liver disease that affects the bile ducts and liver 1,2. In PSC, the bile does not flow properly due to obstruction/narrowing (strictures) in the bile ducts inside and/or outside the liver.

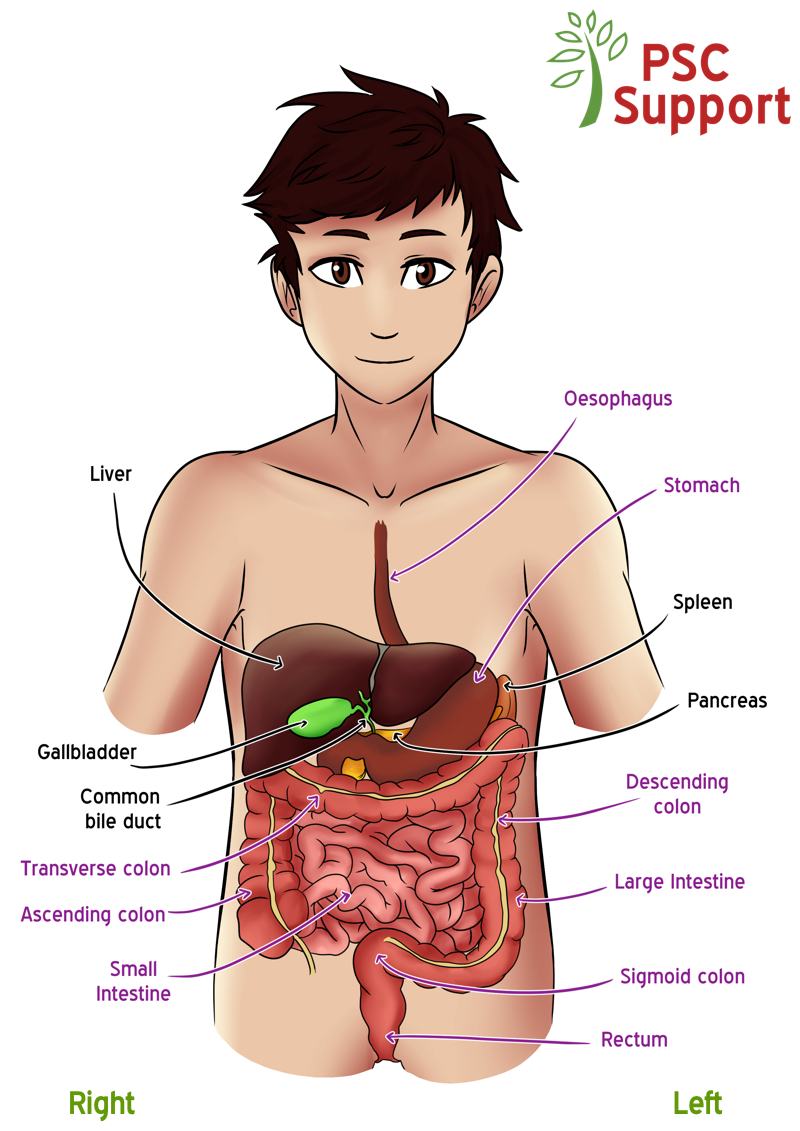

The liver is an organ in the body located in the tummy, just under your ribcage on the right-hand side (also known as the upper right quadrant). See figure 1.

Figure 1. The liver and bile ducts in PSC.

Illustration credit: PSC Support/Becci Such

Bile ducts are a tubular system which are inside the liver as well as some main tubes emerging outside the liver, and they drain bile.

Bile is a greenish-yellow fluid produced by the liver to help digest fats and doctors are now realising that it has many other important functions in the human body. Some of the bile is stored in the gallbladder. Bile drains out from the liver and gallbladder into the small intestine through a network of different sized tubes that are found inside and outside the liver, called the bile ducts.

The bile ducts have different sized diameters, and so are ‘large’ or ‘small’ bile ducts. Generally, the small bile ducts are only present inside the liver, and the bile ducts which emerge from and are outside of the liver are large bile ducts.It helps to think of the bile ducts as a tree. Outside of the liver is the trunk, and as it enters the liver it divides and divides (like branches of a tree) until you reach the smallest tubes of the bile duct inside of the liver.

PSC is an immune related condition. The function of our immune system is to protect us from pathogens that can invade our body from the outside world, such as bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites. However, in some individuals, the immune system goes wrong and instead of protecting us from pathogens, it turns against us and attacks our own organs, causing ‘autoimmune diseases’. In people with PSC, the inappropriate immune-mediated damage is targeted at our bile ducts, either inside (intrahepatic) or outside (extrahepatic) the liver. In certain cases, both intrahepatic and extra hepatic ducts are involved.

In some people with PSC, this inappropriate immune attack is not just confined to the liver. In around 75-80% of patients, there is also an attack on the lining of the large bowel wall. This is referred to as inflammatory bowel disease, and in most cases occurs in a pattern described as ulcerative colitis (UC). This type of colitis is unique and is different to the colitis that occurs in people without PSC. On the other hand, only about 8% of people with IBD develop sclerosing cholangitis 3.

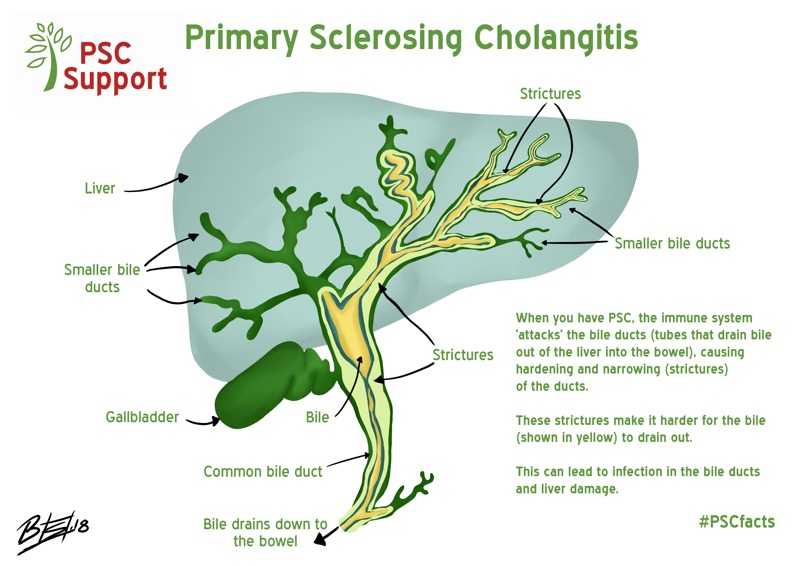

In people with PSC, the immune system ‘attacks’ the bile ducts, causing inflammation (cholangitis), which results in hardening and scarring (sclerosing) which makes the ducts get narrower 1, causing what, in medical terms, is defined ‘cholestasis’. See figure 2. This means that the bile cannot drain out properly and it builds up. This can also lead to infection in the bile and ducts ( see bacterial cholangitis) and the liver trying to heal itself by laying down scar tissue. Over time, this scar tissue in the liver can progress from mild scarring to moderate scarring and finally to cirrhosis, for some people.

Figure 2. The liver and bile ducts in PSC

Illustration credit: PSC Support/Becci Such

This scarring or hardening in the bile ducts is referred to as a bile duct injury, and can cause a blockage or a stricture, which is effectively a reduction in the diameter of a bile duct. In PSC, strictures can develop in any size of bile duct 4.

In some people with PSC, these strictures can be seen on a type of MRI scan called an MRCP, in which case it is referred to as large duct or classical PSC. However, in others, the strictures are only in the tiny bile ducts and cannot be seen on MRCP (referred to as small duct PSC). For this reason, small duct PSC can only be diagnosed by liver biopsy.

Let’s return to the tree analogy and imagine the trunk of the tree representing the largest bile duct (common bile duct), and the twigs at the end of the branches representing the small bile ducts. The bile needs to drain down from the many small twigs (small ducts) down to the bottom of the thick trunk (common bile duct) and out into the duodenum, the first part of the small intestine. But the strictures make the bile flow difficult. This impairment of bile flow in the damaged tubes and build-up of bile in the ducts is often referred to as ‘cholestasis’ by doctors.

A blockage or stricture located in the trunk or larger branches (ducts) can cause more problems to bile flow than blockages in the smaller twigs, because a blockage in the trunk means the bile has fewer options for draining out. On the other hand, when there is a blockage or stricture in one of the many twigs (small, intrahepatic ducts), the bile can still drain out of one of the many other unblocked twigs.

Many thanks to Perspectum Diagnostics for creating this video especially for PSC Support.

This MRCP video shows a 3D image of the bile ducts in a healthy person (left), and a person with PSC (right). The areas of scarring in the PSC bile ducts appear as uneven lump and bumps. It is much more difficult for the bile to flow through the PSC bile ducts compared to healthy ducts.

Note, you can see more of the smaller bile ducts in the PSC bile ducts. This could be because smaller (intrahepatic) bile ducts get become dilated in PSC and are then visible in MRCP images.

A stricture measuring less than 1.5mm diameter in the common bile duct, or less than 1mm in the left or right main hepatic duct, within 2cm of where they join together, is called a dominant stricture (DS). Dominant strictures usually cause symptoms, usually including once or more of the following: itching, jaundice (yellow colour of the skin), right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain, cholangitis, worsening biochemical tests. Any new, symptomatic DS should be thoroughly evaluated by your PSC doctor 5.

In certain circumstances, your doctor may arrange an ERCP (Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) to help unblock the ducts. There are some risks associated with this procedure and the decision is never taken lightly, but sometimes it is necessary to try to help your bile flow. The judgement as to when ERCP is required is complex and will usually require a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) discussion.

What is the Cause of PSC?

PSC is a complex liver disease and we don’t fully understand what causes it

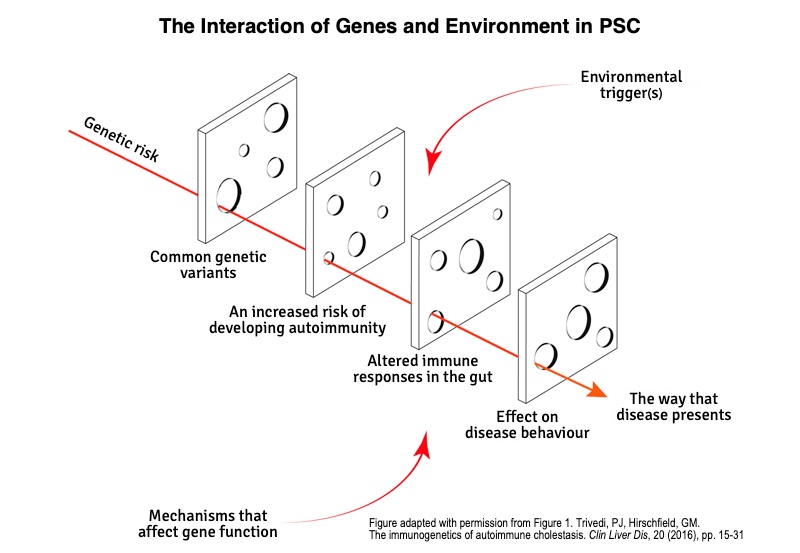

Current evidence suggests PSC is caused by a combination of multiple genetic changes in our DNA and so far unknown environmental triggers making an individual prone to immune attack 13. This means that people with a particular genetic makeup may be sensitive to some sort of environmental trigger that causes their immune system to ‘attack’ their bile ducts. We’re not sure what that trigger is. It could be diet, exposure to toxins, infection, microbiota (the bugs that live inside us) or even a combination of all these factors 14.

There is currently more research investigating our condition than ever before, so we’re hopeful that one day we will understand the exact cause of the disease. Understanding the cause of PSC and how it develops may help scientists to define strategies to interrupt that process and treat PSC. It is possible that drugs already available for other diseases could one day be used to treat PSC 2. This is called ‘drug repurposing’.

This talk was originally broadcast live onto Facebook. We've split it into shorter videos. You can find the whole series on YouTube.

The genetics of PSC have been studied closely using an approach called genome-wide association studies (GWAS). This involves scanning complete sets of DNA to find genetic variations that are associated with a particular disease. Once new genetic associations are found, it is hoped that researchers will be able to use the information to develop better strategies to detect, treat or even prevent the disease.

GWAS have shown that PSC is not caused by a problem with a single gene but that there are 23 regions in our DNA associated with PSC 2,15 and has confirmed that PSC may be described as an autoimmune disease 2. Despite these findings, this genetic element explains less than 10% of the risk of developing PSC 16, suggesting that environmental factors play a key role.

More on the results of the PSC GWAS

If you'd like to know more about genetics and PSC, Dr Simon Rushbrook gave an excellent talk about why genetics are so important including a mini genetics lesson to help us understand:

The interaction between genes and the environment in PSC is complex. The genes linked with PSC (the genetic risk) may affect how your immune system responds to environmental trigger(s) or influence further changes in the body over time. The interaction of these factors can be visualised as a pathway that results in PSC. See Figure 1. 17.

Figure 1. The Interaction of Genes and the Environment in PSC

The gut microbiome refers to a collection of different microbes in the digestive system (intestinal microbiota), such as bacteria, yeasts, fungi, viruses and protozoans. In PSC there are abnormal changes in the types and numbers of intestinal microbiota. This is called dysbiosis 18. A number of small studies suggest that 1) there is a distinct gut microbiota profile in PSC 19 and that 2) there is not as much variety in gut microbiota present in people with PSC compared to people who do not have PSC and compared to people with IBD only 20.

As discussed above, we do not yet know whether this has something to do with the cause of PSC or whether it is a consequence of having PSC (akin to the chicken and the egg scenario). Larger-scale research in this area is needed 20,21. It is possible that in the future, the distinct gut microbiota pattern seen in PSC could help distinguish PSC-IBD from IBD alone, or help identify early-stage PSC 20. It is possible that manipulation of the gut microbiome could provide a treatment for PSC 21 but caution is urged by Professor Tom Karlsen who warns that manipulation could also affect the protective elements of intestinal microbiota 20.

Dr Kate Lynch (née Williamson) explains microbiome research and emerging results and challenges in this video (watch from 4m15s):

Who gets PSC?

PSC is a liver disease that anyone can get, at any age 22, but it is rare.

PSC is a rare disease

According to Rare Disease UK, a rare disease is a disease that affects less than 500 people per million (or less than 1 person in 2000).

How many people have PSC?

It is difficult to truly calculate how many people have PSC because of differences in health records and data collection from country to country. In the UK there could be as many as 10,500 people living with PSC but estimates vary.

The latest figures from the University of Birmingham show that PSC is indeed rare, affecting only around 80 people per million in the UK (prevalence of PSC) 23. Other studies suggest it is even lower at only 56 people per million 24.

There is a geographic pattern of PSC with numbers decreasing from Northern Europe towards Southern Europe 10. A study looking at a number of different countries reported varying numbers of people with PSC in each country ranging from 0 (no one affected) to 162 cases per million people 25.

Of course, it might also be the case that a number of individuals with colitis may also have as yet undetected PSC. In fact, studies have suggested that perhaps 8-14% of people with colitis and normal liver blood tests have changes in their bile ducts that are associated with PSC (when their bile ducts are closely examined) 3.

How many people are diagnosed with PSC each year?

The number of people diagnosed with PSC each year is called the incidence of PSC. It is reported that around seven people per million get diagnosed with PSC each year in the UK 23,24. The number of new cases each year is thought to be increasing, perhaps because PSC is being diagnosed at an earlier stage or because we’re becoming more exposed to environmental triggers (or that our exposure to protective factors is decreasing) 15.

PSC and smoking

Interestingly, people with PSC are usually non-smokers 1,10,24. In fact, studies looking back on people’s health records suggest that smoking could even have a protective effect against the development of PSC 26. However, cigarette smoking is harmful to your health, even at low levels of consumption 27,28 and one of the biggest causes of deaths in the UK 29 - you should not take up smoking.

PSC and alcohol

Getting PSC is not associated with drinking alcohol. A study investigating the relationship between possible environmental factors and risk of developing PSC found that people with PSC reported lower alcohol consumption both at the time asked and back when they were 18 years old 1. Having said that, most doctors suggest that if you have PSC you have no alcohol, or minimal alcohol, as any alcohol can accelerate pre-existing liver damage.

PSC and coffee

Some recent studies reported that people with PSC generally drink less coffee than control subjects, suggesting that coffee consumption may be associated with a reduced risk of developing PSC 26,30, as well as a slower progression of the disease 31. However, these data need further validation.

More men than women have PSC

PSC is diagnosed in up to twice as many men as women 23,32. However, some researchers are beginning to believe that PSC occurs as commonly in females as in males, but that there may be fewer signs or symptoms in females 2 so it may remain undiagnosed 3. The disease seems generally to have a milder course in female patients than in male 7.

PSC can affect people at any age

Most people with PSC are diagnosed between 25 and 40 years of age, although it can be diagnosed at any age, and is recognised as an important cause of chronic liver disease in children 22,23.

PSC and socioeconomic deprivation

No relationship between new cases of PSC and socioeconomic deprivation has been found. This is important to note because this does appear to be the case for another immune-mediated bile duct disease, PBC (primary biliary cholangitis). In PBC, certain aspects of socioeconomic deprivation may be involved in the development of the condition 33.

This is the most common question we're asked when someone has a diagnosis of PSC.

Because PSC is highly variable between patients, it is not possible to predict the symptoms you will experience, how often or how severely. In fact, many people with PSC don’t show any symptoms (asymptomatic) when they are diagnosed. Also, symptoms seem to come and go over time for some individuals. For this reason, your medical history is important in order to establish whether your current symptoms are part of the regular pattern of your disease or if they represent a sudden deterioration. Only around half of people with PSC ever need a liver transplant 7. Despite that, patients and their families understandably struggle with the uncertainty, and want to know what is likely to happen to them 35, what stage their liver disease is at and the life expectancy is for someone with PSC.

Many people with PSC worry that their children will ‘inherit’ PSC because genetic changes contribute to the development of PSC. First degree relatives of people with PSC are thought to have a 0.7% prevalence of PSC 34. So, while first degree relatives are slightly more likely to have PSC, it is worth noting that PSC is not subject to the classic Mendelian inheritance laws we learnt at school 17 and it is very rare to see PSC run in families. At the present time therefore, we do not suggest screening for PSC in family members with no symptoms.

Because PSC can cause damage to the bile ducts and to the liver itself, it is not strictly correct to consider stages of disease in PSC. It is more appropriate to consider the damage to the bile ducts and liver separately, because some people have very badly damaged bile ducts yet have a liver with little or no damage. Equally, the bile in the bile ducts can be flowing well, yet the individual has advanced liver damage. Other people have both bile duct damage and liver damage. Disease progression in PSC is an individual matter and often difficult to predict. Your doctor will consider your medical history, imaging results (MRI or other scan), blood test results, other measures such as Fibroscan results (a test used to evaluate how much scarring there is in your liver) and, of course, how you feel, to determine how well you are.

Interest within the PSC community is growing in being able to predict what will happen in the disease course of people with PSC. One of the most common questions we are asked is, ‘What will happen to me?’ It is difficult to answer because of the complexity of PSC.

The largest ever group of PSC patients was studied by the International PSC Study Group (IPSCSG) spanning 30 years of medical records and 17 countries 7. They not only identified factors that affect rate of progression of PSC, but also how and to what extent they may impact the clinical course of PSC. This study was a major breakthrough in our understanding of PSC and its impact on patients. Given the variation in PSC between patients, these groupings could prove important in identifying those who need closer clinical management and for selecting and studying patients in research studies.

A prognostic tool is something that can be used to predict what will happen to you. For PSC, prognostic tools tend to be a collection of measures and tests such as blood tests and location of damage in the bile ducts. Researchers have studied thousands of patient health records and biological/imaging test results to determine what clues might predict the progression of your disease or how likely you are to need a transplant in the future.

Variants of PSC

PSC is a complex and varied condition with different ways of presenting itself. These different forms of PSC are called ‘subtypes’ or ‘variants’. A number of forms of PSC have been proposed because of differences between patients based on the location of bile duct damage, having inflammatory bowel disease or not, different immunology on blood testing and even risk factors for progression of the disease 6,7.

There are three well-established subtypes of PSC 8:

- Classical or large duct PSC

- Small duct PSC

- PSC with features of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), also known as 'overlap' syndrome

Other types of PSC include:

- PSC with no IBD

- Recurrent PSC (rPSC)

When blockages are evident in both the large and small bile ducts of the biliary tree, the PSC is called ‘classical PSC’. If your doctor hasn’t told you what type of PSC you have, it is likely that you have classical PSC.

When blockages are only evident in the smaller, intrahepatic ducts of the biliary tree, the PSC is called ‘small duct PSC’. People with small duct PSC tend to have a milder disease which progresses more slowly and has lower risk of hepatobiliary (liver, gallbladder and bile duct) and pancreatic cancers than those with strictures in larger ducts (‘classical PSC’) 6,7.

Less than 10% of people with PSC have small duct PSC 9. It is not clear whether small duct PSC really is a PSC variant, or whether it is early stage PSC 2 because in around a fifth of people with small duct PSC, the large ducts will eventually become affected as well 1. For this reason, people with small duct PSC are monitored for any deterioration such as a sudden rise in their liver blood test results (alkaline phosphatase (ALP) or bilirubin), or sudden new symptoms) 10.

In small duct PSC where IBD is not present, other diseases will also be considered and ruled out as there are some diseases that can mimic small duct PSC e.g. primary biliary cholangitis or secondary sclerosing cholangitis which can normally be ruled out by a combination of a detailed history being taken and some blood tests 1.

In PSC with features of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), the inappropriate immune attack seems to go further than just attacking the bile duct cells.

In this condition, in fact there also seems to be immune-mediated damage of the cells of the liver called hepatocytes 10. When this is present, doctors will often prescribe drugs to suppress the immune system, including corticosteroids.

People with PSC and features of AIH rarely develop cancers in the biliary tract, but experience a similar rate of liver disease progression compared to classical PSC 7.

Most people with PSC have inflammatory bowel disease (around 80%) which may be detected before, at the same time or after the diagnosis of PSC, or even after a patient has undergone liver transplantation. Some individuals have no evidence of inflammatory bowel disease however, this is not always clear because it is possible that these people may in fact experience very mild colitis which is simply undetectable by current techniques 11.

A recent large-scale study showed that PSC without IBD was associated with a lower risk of liver disease progression and a lower risk of developing hepatobiliary cancer than patients with ulcerative colitis 7.

If you don’t have IBD, and you’ve been diagnosed with PSC, you should expect to have a full colonoscopy with biopsies so that your bowels can be properly checked for IBD 10, which can sometime be silent (without causing any overt symptoms). The absence of any bowel symptom does not exclude the presence of IBD.

If PSC returns after you have had a liver transplant for PSC, it is called recurrent PSC (rPSC). This happens in around a quarter of people who have had a liver transplant for PSC 10, although this figure is hard to confirm, because rPSC is difficult to distinguish from the complications that can occur in the bile ducts following the transplant surgery 12.

A combination of imaging, histology (biopsies) and blood tests are used to diagnose rPSC.

Some research suggests that having a colectomy (the surgical procedure to remove all or part of your colon) before or at the time of liver transplantation may have a protective effect on the development of rPSC but there is not enough evidence at this stage to recommend this course of action 12.