Liver transplantation for PSC

Your guide to liver transplantation

For information about liver transplantation during the COVID pandemic, see our dedicated COVID page.

PSC causes damage to the bile ducts, and damage to the liver. For some people, a liver transplant is considered to treat the effects of the bile duct damage or liver damage. In fact, 10%–15% of all liver transplants in Europe are now for PSC 7. People with PSC have an excellent outcome after liver transplant compared to those with other liver diseases 2.

Professor David Adams describes having a transplant with PSC as giving a ‘new lease of life’.

Liver transplant relies on organ donation. PSC Support is working hard to raise awareness of the importance of organ donation and having a conversation with family and friends about it.

Not everyone with PSC will need a liver transplant

A large international study of over 7,000 people with PSC found that less than half needed a transplant 7. Everyone with PSC experiences the disease differently; no single person has the same symptoms, biliary damage, associated IBD or rate of progression 78. PSC can advance at different rates, rapidly in some people, and slower in others 7 so it is very difficult to say who will need a transplant.

In general, one of the following situations could indicate it is time to assess your suitability for liver transplant 80:

- a very badly damaged liver; or

- constant and repeated, uncontrolled bile duct infections (recurrent cholangitis); or

- persistent itch (intractable pruritus) that cannot be controlled with medicines.

In the UK, fatigue and bile duct cancer are not accepted indications for liver transplant but the issue of bile duct cancer is being looked at by Professor Nigel Heaton in conjunction with the NHSBT Liver Advisory Group.

As part of your routine care, your PSC doctor will monitor your symptoms and liver function, and if the disease has progressed, will refer you to a liver transplant unit to be assessed for your suitability for liver transplant. This is called a liver transplant assessment.

In the UK, doctors use scoring systems to indicate when a patient is likely to need referral to a liver transplantation unit. The score referred to is UKELD. In countries outside the UK, you will see similar approaches used but the scoring system is different. One such scoring system is the MELD score. Nonetheless, the principle is the same: both inform doctors when the degree of liver failure merits consideration for liver transplantation. Once a patient has reached a UKELD greater than 49, discussions should already be taking place about the possibility of liver transplantation.

A live donor liver transplant (LDLT) is when a living person donates part of their liver to a person on the liver transplant waiting list. The donor’s liver, unlike other organs, is then able to regrow (regenerate) within 12 to 16 weeks. LDLT operations have been successfully taking place in the UK since 1995 and PSC patients do very well indeed after LDLT 2.

Usually, livers for transplantation come from people that have died. However, the number of patients on the national waiting list for a new liver is growing, and there are not enough donor organs to meet demand. Because of this organ shortage, the wait for a liver can sometimes be long, and sadly, some people die whilst waiting or become too sick to undergo the operation. Lots of work is being done to raise awareness and to encourage a positive attitude from society towards organ donation, in order to increase the number of people who have signed the Organ Donor Register. However, until there are enough organs to go round, LDLT is an option for some people who are on the waiting list.

LDLT can reduce the time you have to wait for your transplant.

The donated portion of liver is likely to be in optimum condition because:

- living donors are fit, healthy and carefully screened before being allowed to donate.

- the surgery is done in a controlled manner, minimising the time that it is without a blood supply.

The LDLT is fully planned, allowing you and your donor to prepare for the psychological,

physical and social effects of the transplant.

A LDLT donor is usually a friend or member of your family. Donating a portion of the liver is a big operation that carries some risks, and the person must be healthy, willing and psychologically ready to be your donor. This brave and amazing decision must be the donor’s and must be completely voluntary; they must not be pressured or do it for money. To ensure fitness, the hospital will give them a full medical assessment. They must also be a compatible blood group 88:

Compatible blood groups

| Your blood group | Your donor’s blood group |

|---|---|

| O | O |

| A | O or A |

| B | O or B |

| AB | O or A or B or AB |

It’s important to understand that not everyone who wants to be a living donor is suitable. Nearly 2 out of 3 potential live donors are not suitable 88. If a suitable donor is found for you, you will remain on the usual waiting list for a liver transplant while you wait for your LDLT operation.

When you donate as a living donor, you usually give between 40 and 60% of your liver.

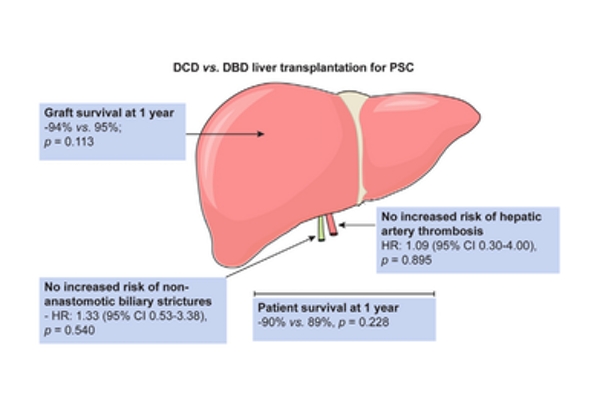

DCD and DBD organs in PSC liver transplant explained

PSC varies from patient to patient, and many go on to live normal lives. Others however, may be affected by symptoms such as fatigue, itch and abdominal pain. Some individuals do unfortunately develop progressive disease, and liver transplantation is the only life-saving treatment at this stage.

Although PSC is a rare disease, it is now the reason for more than 11% of all liver transplant operations performed in the UK 93 - second only to alcohol-related liver disease and liver cancer.

DCD and DBD organs for liver transplant in PSC. Image courtesy of authors (Journal of Hepatology).

Best use of available organs

Thankfully, the number of transplant operations being performed year-on-year are increasing, together with a rise in donor registrations. However, the supply of suitable donor organs does not meet demand. Researchers are thus constantly looking for ways to make the best possible use of available organs.

DCD vs. DBD organs

The most common source for a new liver is one retrieved from an individual whose heart is still beating, but brain has ceased to function - termed organ donation after brain death 81 (DBD). The reason for DBD liver being ideal is because the liver is receiving an adequate supply of blood, nutrients and oxygen up until it is taken for transplantation. Less commonly, liver transplantation may have to be performed using an organ donated after circulatory death 82 (DCD).

Historically there has been a perception that post-transplant outcomes are worse using DCD livers, given that the organ would experience a period without an adequate blood supply, effectively starved for some time before it is retrieved. As a result, early experiences of DCD livers particularly in very sick individuals, raised concerns over transplant-related bile duct problems, kidney injury, and poor overall graft function.

These anxieties are particularly relevant for patients with PSC who are often quite young and have lived with bile duct disease for many years. Consequently, many liver transplant centres across the world have avoided DCD livers in PSC liver transplantation, despite the fact some patients die on the transplant waiting list.

Nevertheless, a study published in 2017 from researchers at University of Birmingham 83 evaluated outcomes of over a decade of liver transplantation, across two groups of PSC patients: those receiving DBD livers vs. DCD transplants. The investigators were able to show that with careful patient and donor organ selection, DCD transplantation in PSC achieves very similar outcomes to those receiving DBD livers.

Highlights from the study included:

- No significant differences between DCD and DBD groups in terms of:

- operation times

- blood transfusion requirement

- number of days spent in the intensive care unit

- total hospital stay following liver transplant

- risk of acute kidney injury

- problems of the transplanted liver blood supply (hepatic artery thrombosis)

- overall patient survival

- overall graft survival / need for a 2nd liver transplant

- A higher incidence of hepatic artery thrombosis in PSC patients who have IBD in both groups (emphasising the need for good colitis assessment and control)

- An increased risk of very early transplant-related bile duct complications in the DCD group, but no difference in the development of biliary complications overall

It’s important to understand that whatever the underlying liver disease, DCD liver transplant recipients tend to have a higher rate of bile duct problems in their first year, and PSC is no exception. The rate of graft loss in PSC was significantly greater compared to non-PSC patients, but looking at PSC patients alone, DCD vs DBD transplantation did not adversely affect overall patient survival or graft survival rates, thus the conclusion that DCD transplants could be a viable option for selected PSC patients in the future.

The use of DCD livers in transplantation is a developing practice, and longer-term outcomes have yet to be determined. Similarly, while the transplant centre at Birmingham is one of the busiest in the UK, this study only represents experience at one centre, and the authors acknowledge the importance of external, independent validation of their findings. However, given the complexity of PSC, and with the forthcoming changes to allocation policy in liver transplantation in the UK, continuing evaluation of risks and post-transplant outcomes for PSC patients is critical.

Originally written by Dr Palak Trivedi and Martine Walmsley 13 July 2017

Traditionally, when the organ is taken out of the donor, the blood is flushed out and it is transported to the recipient packed in ice.

With machine perfusion, the liver is connected to the machine, oxygenated and the function of the liver is measured. It is believed that this method helps preserve the liver while in transit and improve the quality of the organ.

The measurements made while on perfusion allows surgeons to transplant livers that were previously not considered to work well enough (because the machine provides data to show that the livers do function well).

Machine perfusion also enables better planning and management of logistics. It allows longer transport times than if transported in ice, which is important now the UK is using a national offering system where organs may need to travel from one end of the country to another.

Liver perfusion is a new technology, and we are still learning about it through research trials. Ultimately, by using liver perfusion technology we hope that the pool of usable organs for transplantation will be increased, time on waiting lists reduced, and more lives saved.

More information on machine perfusion

Game changer for liver transplantation

'Warm transplants' save lives and livers

Machine Perfusion Improves Donor Livers (June 2020)

VITTAL Study Summary (August 2020)

Oxford University surgical lectures: Machine perfusion – a new dawn or optimistic hyperbole?

A number of factors affect how well your new liver will function. It can depend on the type of liver transplant you have, the type of liver you receive and even factors associated with the liver donor themselves.

People on the liver transplant waiting list can be offered three types of liver, DBD, DCD and LDLT:

- DBD (donation after brain stem death) - the new liver is one retrieved from an individual whose heart is still beating, but brain has ceased to function 81. The DBD liver is usually seen as being ‘ideal’ because the liver receives an adequate supply of blood, nutrients and oxygen up until it is taken for transplantation.

- DCD (donation after cardiac death) - less commonly, liver transplantation may have to be performed using a DCD organ 82. DCD liver transplant recipients tend to have a higher rate of bile duct problems in their first year, and PSC is no exception. A 2017 research study 83 found that for PSC patients, DCD vs DBD transplantation did not adversely affect overall patient survival or graft survival rates, suggesting that DCD transplants could be a viable option for selected PSC patients in the future.

- LDLT (donation from a living person) - becoming more common, a person donates part of their liver to you. People with PSC who have a LDLT do very well indeed, better than those who receive organs from deceased donors 2.

Sometimes part of a liver from a deceased donor is put into an adult and the other part into a child (or small adult). This is called a split liver transplant.

The quality of the donor liver is affected by factors relating to the donor themselves; some donors are fit and healthy while others are overweight with a fatty liver. The new organ allocation system takes into account these factors to ensure the right liver is donated to the most suitable person on the waiting list.

In an ideal world, everyone would receive the ‘perfect organ’, but due to the lack of organ donors and the increasing number of people waiting for a transplant, this isn’t always possible. The important thing is to consider the liver that is right for you at that time. Your transplant unit will go through the different types of liver you might be offered and explain any additional risks and benefits associated with those livers.

Impact of colectomy type following liver transplant for PSC

A research paper was published in June 2018 by a team led by Dr Palak Trivedi (University of Birmingham), looking at the impact of colectomy type following liver transplant for PSC. When colitis does not respond to medical treatment, you may be offered surgery to remove the large intestine (an operation called ‘subtotal colectomy’).

A research paper was published in June 2018 by a team led by Dr Palak Trivedi (University of Birmingham), looking at the impact of colectomy type following liver transplant for PSC. When colitis does not respond to medical treatment, you may be offered surgery to remove the large intestine (an operation called ‘subtotal colectomy’).

Following the first stage of a colectomy, individuals are left with an ileostomy (stoma), whereby stool from the small intestine left behind empty into a bag attached to the abdomen/outside of the body. However some patients chose to have their stoma joined back to a small remaining part of large intestine at the very tail end / near their bottom (anus). This additional step, wherein the bowel is joined back to continuity, creates what is called an ileal-pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA).

Dr Trivedi found that people with PSC who needed colectomy and retained an end ileostomy experienced fewer complications related to, and after, liver transplantation compared to those who underwent formation of an IPAA.

In addition, patients choosing to keep their ileostomy intact had the lowest risk of needing another transplant, developing PSC recurrence or problems related to liver transplant blood supply compared to the IPAA patient group or those who did not undergo colectomy.

These new findings suggest that keeping an end ileostomy may be protective to the liver following transplantation for PSC. This protective effect was not found for patients needing colectomy who then go onto have their bowel ‘re-connected’ with an IPAA.

The authors speculate that one of the reasons these differences may arise is because there are more episodes of gut inflammation in people with PSC and IPAA (who often develop pouchitis) than in those with an end ileostomy.

While further research is needed, these research findings are important as they allow patients and their healthcare professionals to take more informed decisions if colectomy is needed, particularly when PSC liver disease can progress to the point of needing a liver transplant down the line.

Reviewed by Dr Palak Trivedi, University of Birmingham,12/06/18

Trivedi PJ, Reece J, Laing RW, et al. The impact of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis on graft survival following liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;00:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14828

With no medical treatment yet for PSC, liver transplant and organ donation are areas of great importance for the PSC community

How do I register my decision?

It is quick and easy to join the NHS Organ Donor Register. Visit www.organdonation.nhs.uk or contact the 24 hour a day donor line - 0300 123 23 23. Let your friends and family know your organ donation decision.

Please join us in raising awareness of the value of organ donation

Organ Donation Week

For a week each September, PSC Support joins NHSBT to help promote the value and importance of organ donation. Look out for local events and social media posts encouraging the general public to consider signing the Organ Donor Register, and importantly, talking about it.

Transplant Anniversaries

We love hearing from people who’ve had a liver transplant for PSC telling us about milestones they’ve reached. If you post on social media about your transplant anniversary or any achievement or experience that would not have been possible without organ donation, please tag us. We love to share these special posts.

- Like our Facebook Page

- Follow us on Twitter

- Follow us on Instagram

- Follow us on LinkedIn

Share your story

If you'd like to share your story with us, so we can feature it on the website and our social media channels, please get in touch to find out more.

Where can I get organ donation leaflets?

If you are raising awareness of organ donation, you can order a supply of organ donation leaflets from the NHSBT website. You can also download digital materials to help you promote organ donation, including social media graphics, smartphone wallpapers and other graphics.

Related news

Kieron Dyer’s PSC Journey

Footballing legend Kieron Dyer shares his PSC journey, talking diagnosis, life with PSC, liver transplantation and recovery

James’s Midnight Ride for a Cure

James, Tim and Al’s Midnight Ride for a Cure Pedalling to accelerate progress towards finding a cure for PSC In the early hours of July 5th, 2024, Oxford resident James and his two friends, Tim and Al, will embark on a unique cycling journey. Starting at 1:30 am from Oxford, they will ride to the…

Organ Donation Week 2023

Monday 18th September marks the beginning of Organ Donation Week 2023. This year’s campaign hopes to see at least 25,000 people register to become organ donors for the first time.

Dan’s Journey from Diagnosis to Transplant to Recovery

Undergoing a liver transplant is a remarkable achievement, yet what follows in its wake? Six months after receiving a new liver, Dan has kindly shared an update on his journey with PSC.